Constructing a Song

Songwriting can be a laborious process for me, and it’s usually spread out over enough time that I forget exactly how the whole thing came about. But I had a small revelation during the writing of one song that prompted me to record my process. The song is called “The Glorious Cause.”

The Kernel

I keep a large file full of lines that come to me. (It’s currently too large, about 14 thousand words.) At some point I wrote these:

They gave us sticks to fight with

when the rest of them had guns.

Where did this come from? I was probably influenced by accounts I had read of Russian troops in the early days of WWII, but there are probably similar cases from WWI and the Civil War.

At some later point, as I stared at those lines, this came out:

And after one battle we all ran away,

just like the hare from the harrier runs.

So this would be a song about desertion. Was that a conscious decision? It may have suggested itself from the first two lines. I like the open and matter-of-fact statement of fear. Of course we ran away. Right there you can tell my sympathy is with the deserter. That was intentional. I’m often attracted to the transgressor or the despised rather than straight, unambiguous heroes and victims. The rhyme is ABCB, which avoids the strong pulse of AABB.

The first two lines could be either verse or chorus, but I felt the last line was the kind of kicker that belongs in a chorus. So I began writing this song with the chorus, which is not unusual, since it’s often the dramatic, chorus-like lines that are the first to pop into your head.

Story

I’m drawn to narrative in songs, and this one especially seemed to need a story. Why do the man and his comrades run away? Well, this one has a wife he wants to go back to. I didn’t want her to be a full character in the story, just a suggestion.

She tied up a packet of fish and potatoes and bread.

She stood at the gate by the road to watch me go.

I said I’d be back before the first snow fell,

but now I just don’t know.

Now I just don’t know.

The rhyme of the verse is ABCBB, similar to the chorus, but with a much different feel. It’s important to note that these stanzas usually do not spring fully formed from my mind to the page. They come in pieces—usually lines, and usually along with a lot of superfluous lines that get discarded.

The scene I’m imagining is of an army marching through the countryside, picking up conscripts like the narrator, people who, unlike the professional soldiers, don’t know what’s happening and don’t necessarily like it. Expanding on that:

Our captain wore a saber and a pair of smooth black boots.

He climbed up on a table and talked about the glorious fight.

Those of us conscripted got a pile of blood-stained boots.

I missed my home that night.

I missed my home that night.

The captain with his saber puts the story in a past time. I don’t think anyone carries sabers anymore.

So now I have two verses and a chorus. A lot of songs have the chorus come in after the first verse, but I usually like two verses before the chorus. Perhaps it’s because I’m usually telling a story and more needs to be told.

Rhythm

The first three verse lines have 5 beats, but there are another 3 silent, or virtual, beats before the next line starts, bringing it to 8. The last two lines are 4 beats, three landing on words and one virtual. The verse, in total, is 32 beats.

The chorus is a mix of 3-, 4-, and 5-beat lines with virtual beats filling them out to multiples of 4. I like having something other than 4 beats in a lyric line, but it turns out that it’s not easy to completely break out of the tyranny of the 4×4 rhythm.

Keeping it Nimble

After the chorus I initially thought of scenes of the narrator running away with his fellow deserters, but I never liked the feel of that. It was becoming too plotted, I think. Excessive plotting and over-explaining can bog a song down and make it seem clunky. After about a thousand words worth of attempts, I settled for a simple description of battle.

The enemy came charging down across the shattered plain.

I didn’t want to die so I fought with great ferocity.

I saw men crying as their blood spilled on the ground.

They looked a lot like me,

a lot like you and me.

The last line seems to be directed at the audience. Ugh. A little bit preachy, that. A little close to protest song territory. But I’ll leave it for now and move on.

Where does one go from here? I thought I needed more justification for his running.

The Break

Yes, this is conventional: verse-verse-chorus-verse-break. Sometimes that’s how it goes. This is a normal place for me to put a break, between a second pair of verses. The break usually contrasts musically and lyrically with both verse and chorus. Here the narrator breaks away from the story to defend his actions. The main part of the song is in Cm; the break modulates to E flat. (I’m not that sophisticated; it’s simply Am and C capoed up.)

I like this break. I like the simple, life-affirming reasons the narrator gives, and I really like the last line, which has the effect of saying, “Look, this is the real reason.”

These are the reasons that I ran—

things they will never understand—

a sunrise lighting up the land,

a wheat field drifting in the wind,

a ripe fig heavy in my hand…

I want to see my wife again.

Different rhyme here also: AAABAB, more or less.

Small Revelation: POV

I don’t remember how this verse came to me, but it was one of those moments where I thought, “Yes, of course, that’s it!” The narrator, it turns out, is not addressing the audience; he is addressing a guard at a river crossing who has the narrator’s fate in his hands.

If you can find it in your heart to look the other way,

I can cross this river and make it home tonight.

Those of us they captured they shot by the side of the road.

Think about what is right.

I’m telling you this is right.

This verse solves the preachiness problem. Of course the narrator is trying to convince the guard (and us, by proxy) of the rightness of his actions; he’s trying to save himself.

Most of my songs don’t really come together until I get a solid sense of character, place, situation, and audience. Here it is a deserter at a bridge trying to convince a guard to let him escape.

The chorus comes in again, reiterating how unfairly the narrator and his fellow conscripts were treated. We are left not knowing the guard’s response.

They gave us sticks to fight with

when the rest of them had guns.

And after one battle we all ran away,

just like the hare from the harrier runs,

just like the hare from the harrier runs.

I wrote the music for “The Glorious Cause” alongside the lyrics. Unfortunately I don’t remember the exact process. Sometimes I will start with a groove (I collect those also), which inspires a set of words, but I’m sure I didn’t do that here. I believe I started adding music when I was working on the first verse.

I’m a fairly basic melodist. I begin with a normal reading of the line and let that suggest both melody and rhythm. I’m slightly more adventurous with harmony, looking for ways to insert unusual chords. In this particular song the most adventurous thing I did was to modulate to the relative major key, which could easily pass unnoticed.

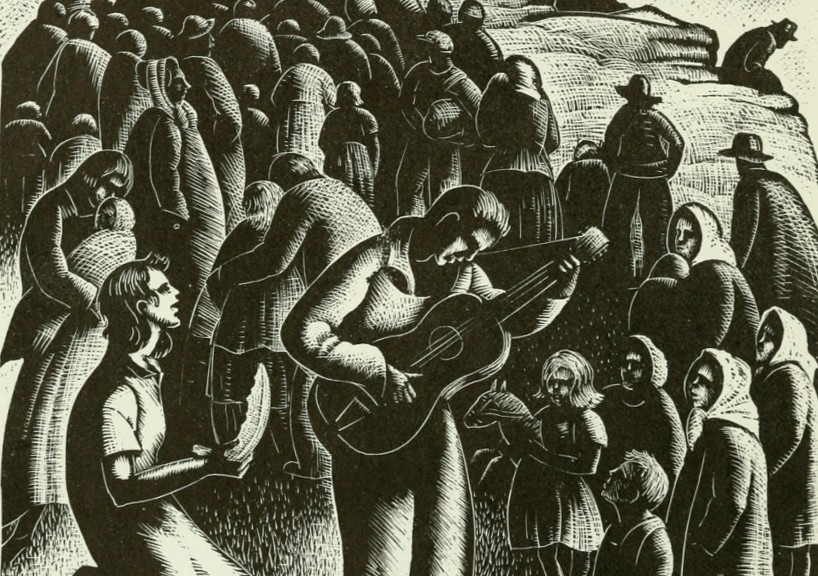

Image: “All Day Singing,” Woodcut by Clare Leighton, 1952. Found at http://blogs.library.duke.edu/blog/2016/01/07/library-receives-grant-to-digitize-early-twentieth-century-folk-music/

Posted on August 19, 2017 at 9:39 am under Words & Music